My Old Material

Let’s now play with the passage of time and the interplay of forgetfulness and memory

One Question

One of the questions about my art that used to irritate me the most was, “Where do you get your material?” Reflecting on this, I think that at the heart of my irritation was just disappointment that a viewer thought to ask this question and wasn’t moved enough by the artwork to ask questions about the work itself. It’s as if asking a question about the source of materials was an admission to missing the poetry of the art. I wonder how many painters get asked at an exhibit, “Where do you get your paint?” Or imagine after seeing a movie, the first question that comes to mind is to ask the casting director, “Where did you get those actors?” or to ask the art director, “Where did you get those particular props?” Interesting questions for sure, but not the kind of queries that typically come to mind fresh after seeing a film that I enjoyed.

But if we add a small phrase to this question and instead ask, “Where on earth do you get your material?” I think it would lead to a better understanding of my relationship to these curated resources. With this altered question, there is no specific physical place where I acquired these things, but rather a nebulous location where they were uncovered—found out. I’ve always sensed that there’s a magical event when these things present themselves to me. We both find ourselves in the same place at the same time. There’s a nagging sensation of a reverse discovery, and that these things are choosing me. I’m also always open to chance and serendipity. These are handy tools for the imagination.

This idea of objects being found gets to another aspect of what I find annoying about that question. My material is always fairly ordinary, common objects and printed matter from our cultural past. I’ve never had to look hard to find this stuff, so when someone asks where I got it, I’m kind of dumbfounded, and I want to reply, “Um, just look around.”

Putting this annoyance aside, I think a potential follow-up question to those irritating ones, and one that I’d rather hear but never do, is, “Why is your material old?” Over the years, I’ve mulled over this question, and I’ve come up with some ideas that I’ll share with you now.

The Past Is Quiet, the Present Is Loud

As the materials of our culture age, our natural relationship with them becomes one of distancing and forgetfulness. We, of any particular present, are mainly concerned with the now, the new, and the novel idea. When we look back on our past, it’s typically either agreeably with nostalgia or negatively with disdain, as when all we see are outmoded ideas. Typically, a derisive tone and a superior posturing accompany the latter: “Can you believe how we used to do that?” I’ve never participated in this, laughing at our inept past, as I can’t help but think how, in a not-too-distant future, they’ll be laughing at us, since we are generally blind to our present absurdities and backward ideas. And for those reasons, when I look at our collective past, I try to employ the neutrality and fascination of an anthropologist. But what interests me more than these older things themselves is how our collective amnesia reveals how the passage of time dissipates the associations we have with these past things. It’s as if these lost associations make these past things quieter, dampening the stories they could tell us, and looking back on this quieter past takes time and concentration to cut through our present-day noisy distractions.

One goal of my assemblages is for people to see the images and objects within them as poetry. That is, to see them not as they appear to be, but rather as they reveal themselves. I try to cultivate the blossoming of new associations. In a way, I’m taking advantage of our forgetfulness by using these things from our past, new enough to recognize and to be somewhat familiar, but old enough that the original intent of what they represented is diminished, if not completely gone. This concept makes me think of watching actors in a silent film, where we need to accept the technical limitations of the medium and stylistic differences of the acting in order for us to appreciate a relatable story. My art is trying to speak through the soft voice of our cultural past, and if you want to hear what it’s saying, you might have to turn down the volume of the present.

The Look and Feel of the Past

In some ways, this might sound like I’m trying to make rational explanations. But I gravitated to this practice of using older material intuitively. In the 1990s, when I was voraciously collecting objects and print material, it wasn’t as if I had a game plan. Never did I have an assemblage project already in progress and then seek out the materials; just the reverse. I’d gather anything that looked like it had potential or was inspiring. Some things just glowed, begging me to take them. These newly acquired objects and images fed my ideas for future boxed assemblage pieces. For example, there was a direct connection between my finding a trove of old illustrated medical books and the consequent assemblages I created once I had time to pore over these thought-provoking images and realize just what I’d accumulated. This would be the series, Anatomy Lesson, which I mentioned in previous Substack posts.

I’m always first drawn to the aesthetic qualities of the objects and illustrations. Books illustrated with lithographs and etchings printed on heavier stock paper, as found in books from the early 1900s, have textures and colors that appeal to me more than newer photographs on glossy coated papers, to name one contrasting example. And in addition to these material qualities, it was the graphic styles that also attracted my attention. The compositional style, colors, and design elements of that era were strange compared to what I grew up knowing, and that intrigued me.

From the shapes of those wooden game pieces to the poses in staged photos in pulp magazines, I felt there was a richer storytelling happening than with similar things from my contemporary life. Perhaps I was responding to the enigma of all things from the past, and I know that I frequently asked myself the question, “Why did they do it that way?” There’s likely a combination of factors that contributed to my acquisition of these things, but I think the underlying truth is that my subconscious has a radar for an undefinable mysterious quality, and that compels me to gather up material like this. Intuition is my prime mover, not only in the activity of making my work, but also in the discovery of the material that will go into it.

Aide-Mémoire

This post has been about how our collective forgetfulness lays the groundwork for my poetic access to the images and objects used in my assemblages. But what if the reason why this works so well has more to do with remembering than forgetting?1 A remembering that’s not a total recall as such, but rather a form of remembering where we conjure a hazy impression. I think it’s a mental activity more related to recalling a dream than a recounting of factual data. We, of the computer age, tend to think of memory simply as a cognitive action of information retrieval. As a mechanistic explanation goes, sure, this works, but I’m more interested in the complexity of processes going on in our minds during the act of remembering. In the case of the material for my artwork, I’m thinking about how images and objects can trigger memories, or even just the summoning up the vague feeling of a memory. I think we do this subconsciously when we have feelings of nostalgia. Nostalgia does not happen in the clear rational mind but is a dreamlike wafting of thoughts that are never entirely distinct. But what if the reason for this mental fog is that there is something more than a one-way path from which we recall something from our well of thoughts? What if there is a back-and-forth connection between us and the image we are looking at? I ask that we consider the possibility that things—objects outside of ourselves—contain their own memory.

Since the time of prehistory, there’s been the cultural recognition of magical objects and sacred relics, things that, under normal circumstances, would be just ordinary objects. When proclaiming them magical, we are imbuing these objects or images with an importance and a privileged position. And when we encounter objects that we are told are sacred, there is a recognition of their power. There are countless stories and fables about these power-infused objects. The thing to bear in mind is that these special objects are never simply magic on their own. The magic is always related to a power to do something wondrous or to evoke something beyond itself, and there’s always a story of how it became as such. This essential story, which is part of this special object, is how they contain memory. There is an easier-to-relate-to, more commonplace practice that most of us do in our daily lives, and that is our relationship with mementos. A literal definition of our connecting memory to objects.

My artwork relies on how ordinary cultural objects have the power of memory. It might be akin to the discipline of anthropology, with its natural history museums filled with shards of pottery, prime examples of anonymous ordinary things. These objects then take on privileged positions as we place them within climate-regulated display cabinets. We are recognizing that these pottery shards retain the memory of the long-dead cultural past that created them.

It’s almost as if our act of forgetting, rather than being a deficit of our functioning brain, is a necessary step for conjuring the memory contained within the object. Magical objects have their power because they contain mystery. And the mystery is not what we know, but what we don’t know. Furthermore, this mystery happens not because we never knew, but because at one time we did have that knowledge, and over time it was forgotten. In this regard, mystery and memory are two sides of the same coin of how we relate to our past.

And It Always Comes Back to a Sense of Wonder

Coming back to the question I started with, of why the material for my assemblage art is from our recent past, it appears to me that the time it takes for memories to fade also allows for mysteries to arise. Seeing things through this haze of forgetfulness is what attracts me to this old stuff. Within the confines of an enclosed assemblage, these past images reflect on one another—sometimes literally with mirrors. My artworks magnify and focus the collected mysteries contained within a box, conjuring in the viewer who is willing to see through the gauze of forgotten memory and achieve a sense of wonder.

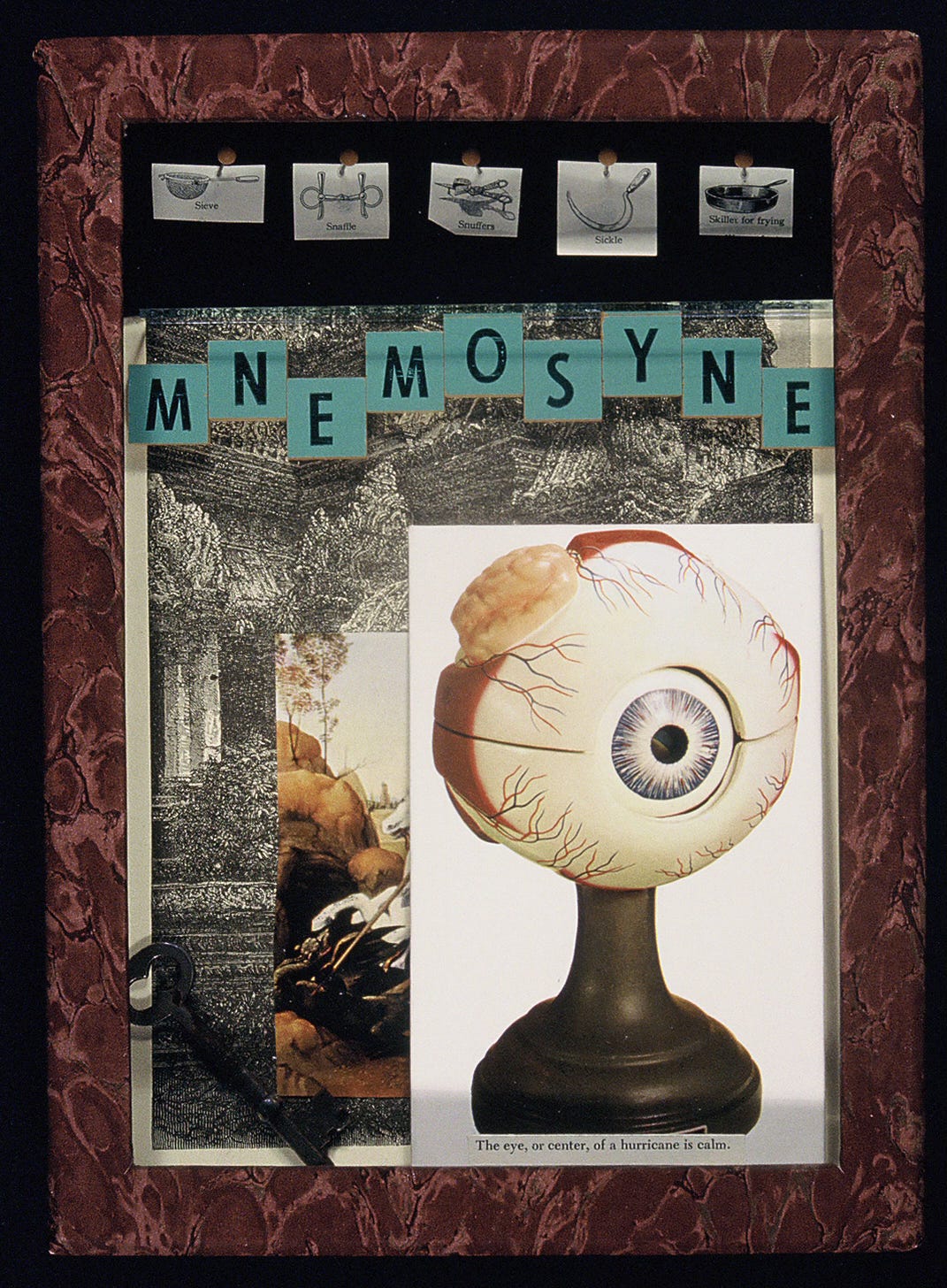

This thought is the seed of a longer essay that I’m working on about the goddess Mnemosyne and her relation to art. Stay tuned.

I so know what you mean about people asking about where you got things. I've been asked where I get my ideas, to which I always reply... "from outer space" ... although outside of being snarky, I wonder if those questions are just an awkward way to try to start a conversation about the work?